In July 1900, Benton Mackaye climbed a tree at the top of Vermont’s Stratton Mountain. That moment, he would later claim, was the origin of what we now call the Appalachian Trail (A.T.). Decades of planning, trail building, and love for the outdoors have since given us the A.T. in its current form.

Videos by Outdoors

This singular trail spans 2,198.4 miles between Springer Mountain in Georgia and Mount Katahdin in Maine. Over that distance, you’ll traverse 14 states, six national parks, eight national forests and two wildlife refuges. According to the Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC), the elevation gain of the A.T. as a whole equals “climbing Mt. Everest 16 times.”

But that doesn’t mean you need Everestian training or stamina to attempt at least some portion of the Appalachian Trail. An experienced A.T. thru-hiker myself, I spoke with a handful of A.T. veterans including Captain Jack, Big Money, Couscous, McGoober, Little Cave, Wizard Spoon, Samwise and Molly Mol to get the scoop.

Who can hike the Appalachian Trail?

An estimated 3 million people visit the Appalachian Trail each year. The A.T. is available to anyone and everyone, but some folks are particularly devoted. Perhaps you’re an aspiring “thru-hiker”—those who attempt to hike the entire trail at once. There are also “section hikers,” who traverse the whole distance, broken up over multiple years. Around 4,000 people attempt a thru-hike each year, the vast majority starting down in Georgia and heading north to the Canadian border.

How much experience do you need to thru-hike the Appalachian Trail?

Fewer than you might think! The term “thru-hiker” refers to anyone trying to hike an entire trail end-to-end. There are many, many long trails one can thru-hike in the U.S., but for most, the A.T. is their first. In that sense, it’s quite accessible.

It’s not easy, though, and setting out unprepared is certainly a bad idea. Approximately 25 percent of people who attempt a thru-hike of the A.T. complete it—which means three-quarters do not. In fact, a huge portion of hopefuls drop out in the first 100 miles. But if you’re interested, you should pursue it! I recommend going out on a few shorter backpacking trips first and seeing how much you really like the lifestyle before committing to the months-long journey.

How long does it take to thru-hike the Appalachian Trail?

The average is 5 to 6 months. One friend of mine, “Captain Jack” Tracy, took over 7 months, from February to October one year. Another friend, Robert “Samwise” Hoffmann, made it in 120 days, from mid-May to mid-September.

The months of March, April and May are solid starting options for northbound hikers, depending on the pace you hope to set. Keep in mind, Mt. Katahdin closes in October when the weather gets bad. Baxter State Park strongly recommends you complete your A.T. thru-hike by October 15.

Start and end dates will vary if a hiker elects to start in Maine and go southbound instead. This could be a good choice for someone hoping for a more isolated wilderness experience, and it can also lessen the ecological impact of thru-hikers on the trail.

Another option that’s growing in popularity is to “flip-flop.” For example, you start at the midpoint, Harper’s Ferry in West Virginia, head north to Katahdin, then drive back to the midpoint and go south to finish. Or, after reaching Katahdin, you head all the way down to Springer Mountain and hike back up to West Virginia.

Can you hike the Appalachian Trail alone?

You sure can! But being uncertain whether or not you’ll make it on your own out there is natural—and it’s incredibly rewarding when you prove that you’re able. That said, there’s such a vibrant community who do it, if you set out alone, you’re bound to find some companions. In fact, finding a “trail family” can be one of the best parts of your thru-hike. Often, the companions you meet along the way will be the ones to give you your trail name, too. It’s most fun when bestowed upon you by other hikers, but you’ll have the final say to ensure it reflects who you are and who you want to be while you’re out there.

What about hiking with a dog? People do it—but must be careful. Truthfully, not many dogs can keep up on a thru-hike. As humans, we have the most efficient gait in the animal kingdom, and dogs’ anatomies just aren’t designed for endurance over long distances. Pups can also maybe carry some of their food, but the bulk of the work lugging their gear will fall to you.

Plenty of people hike with their partners, too, and it can be an incredible shared experience. However, you’ll see each other at your lowest, you’ll occasionally get sick of each other—and you’ll both have to decide independently if thru-hiking is something you really, really want. Whether you’re hiking with a romantic partner or a friend, I’d advise that you ensure you’re both able to operate independently on the trail. Sometimes, a day or two hiking apart from each other is all you’ll need to come back together refreshed.

What gear should you bring to hike the Appalachian Trail?

There’s a lot that goes into a gear list. The weight of each item is vital, as every ounce counts. That said, Tessa “Big Money” Babcock reminds you to get what works for your body and you. You’ll receive a lot of unsolicited advice on the trail. Some of it will be good advice, and some of it will not. You know best what you need.

Here’s a good starting rule of thumb: Ideally your shelter, your sleeping pad, your sleeping bag and your backpack weigh under 10 pounds combined. For more specifics, you can find an infinite number of gear lists online that can help guide you.

If there’s one thing you choose to focus on, Big Money says, “Splurge on your sleep system—it’s your bedroom until you finish the trail. Make it cozy, make it homey!”

You’ll want to have a way to keep your gear dry, too; a pack cover or a garbage bag to act as an internal shell.

Beyond that, be flexible. Take a few overnight hikes with your full pack before you set out. Bring only what you need. You’ll inevitably pack a little too much and learn quickly what you can do without.

What should you wear for hiking the Appalachian Trail?

First and foremost, you’ll want layers. You also should have clothes to hike in and clothes to sleep in. Invest in a nice raincoat (or poncho), a base layer, and a nice packable “puffy” for insulation. The rest can probably be thrifted—your hiking clothes will get filthy, I promise.

“Be bold, start cold,” you’ll hear people say as they set off wearing short shorts and a tattered button-up on a chilly morning. The idea here is that hiking will warm you up, and you won’t have to stop to remove your layers as you go. You want your trail wardrobe to be flexible and utilitarian while still expressing how crazy you are for attempting a thru-hike. Marcus “Wizard Spoon” Carroll, who will be setting out on the A.T. in 2023, says he’s planning to don a floral shirt with matching pants and hat. While Captain Jack says they like to look like “a steampunk Pokemon trainer: sun gloves, baseball cap, glacier goggles.”

What shoes are best to hike the Appalachian Trail?

One of the most important factors in a thru-hike is what’s on your feet. Fair warning: You will need to “break in” your feet—not just your shoes. In almost any pair, you will get some blisters that will turn into calluses (yet another reason to do some training hikes beforehand).

When choosing your footwear, bear in mind the three things that cause blisters: friction, heat and moisture buildup. The right shoes and socks will help you get as few as possible. The best blister care is preventative, so if you feel a “hot spot” in your shoe as you’re walking, stop and take them off. If you have time to dry your feet out, do so, and tape over your skin where you were feeling the burn. Leukotape or KT Tape will stay well despite your sweat.

Everyone’s needs and feet are different, but nearly all thru-hikers skip traditional hiking boots in favor of trail runners—lightweight, breathable sneakers with hiking tread. Why? A pound on your feet is 5 pounds on your back. Merino wool socks will help wick sweat away and cut down on moisture (and they’re naturally antimicrobial, which will help prevent the stink). Shoes with sock liners can help, too, as they prevent friction.

Avoid shoes with waterproofing—if it keeps water out, it keeps water in, and that contributes to moisture buildup. Kim “McGoober” Piscadlo suggests, “Try on lots of shoes until your feet tell you they are happy in them.” Don’t get shoes that are too small, as “Molly Mol” Gibson did. She said, “I cried every time I had to put them on or take them off…this all went on for about the first two months of trail until I replaced my boots.”

Can you get lost on the Appalachian Trail?

Though technically possible, you’re not likely to. The A.T. is well-marked by white rectangles called “blazes.” You’ll see them on trees, posts, rocks and more. Spotting for these is the easiest way to be sure you’re going in the right direction. You may also notice blue blazes that denote side trails—perhaps to a water source or a campsite or to show you the way around a particularly difficult climb. You’ll find an ongoing debate on the trail between “white blazers” and “blue blazers.” It boils down to a question you’ll have to answer for yourself: Is a thru-hike only valid if you stick to the official trail? Or is the thru-hike trail wherever you walk, as long as you get there?

That said, it’s not impossible to get turned around. Big Money has exited a sheltered area and immediately gone the wrong way. If you’re tempted to follow a blue blaze, how do you ensure you find your way back to the A.T.? Plenty of thru-hikers use GPS, most commonly an app called FarOut. There are paper guides available as well: The A.T. Guide by David “Awol” Miller or the ATC’s own book, The Thru-Hiker’s Companion, are good options.

What about food and water?

You’ll eat anything shelf-stable that’s not packaged in metal or glass, and you’ll want to eat a lot of it. After a couple of sections, you’ll develop “hiker hunger” in which you become a bottomless pit starving for calories.

What’s for breakfast? Perhaps some almonds, a granola bar or two or three, some instant coffee, a toaster pastry. What’s for lunch? Well, here’s the secret. You don’t have just one lunch. If you’re not walking, you’re eating. And dinner? Good to end your day with a big, high-carb meal.

Commercial backpacker meals are nice but expensive. More commonly, you’ll see thru-hikers cooking instant ramen or Knorr sides in their tiny titanium pots over their ultralight camp stoves. As for water, you’ll need a filter or a purification system that allows you to drink from the streams you pass.

What about when I need to resupply?

One of the nice things about the A.T. is how frequently you’re able to stop into a town. Keep an eye out for food along the trail; Samwise says, “New England deli-to-deli hiking is the cat’s pajamas.”

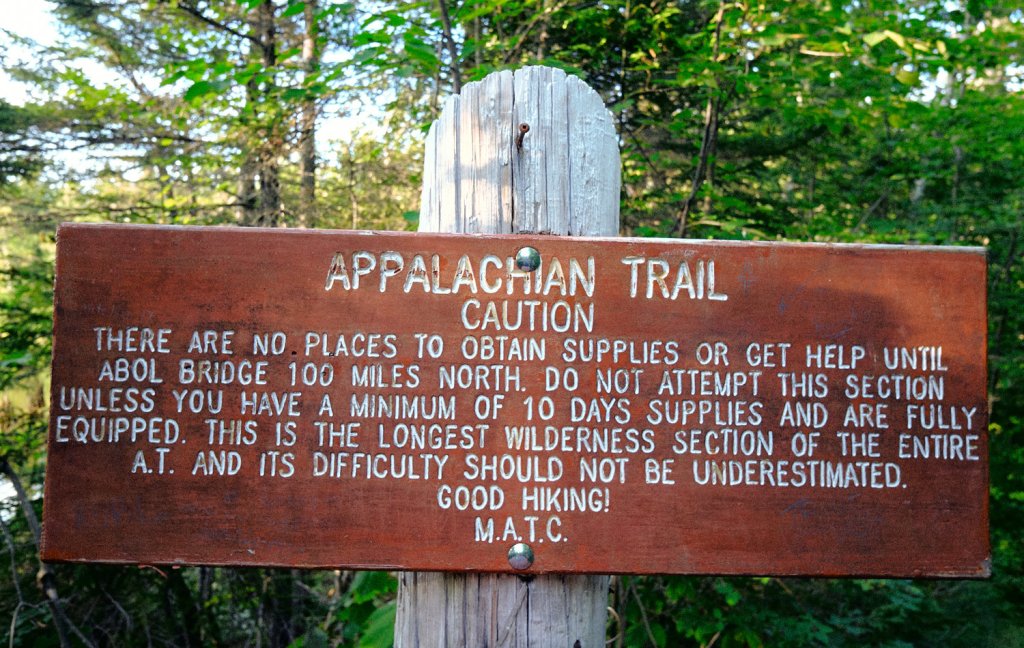

The longest “carry” you’ll need to prepare for is known as “the Hundred-Mile Wilderness” in Maine. If you’re going northbound, you’ll be able to make it in 4 to 5 days at that point.

In one sense, a “thru-hike” is just a bunch of small backpacking trips strung together. The difficulty with resupplying is that you don’t often just walk in and out of town along the trail. More often, you’ll reach a road and need to find your way to town from there. In this case, most people hitchhike.

Is it safe to hike the Appalachian Trail?

The A.T. is a wilderness experience and therefore there is no guarantee of safety. Anything can happen! When I asked Kyle “Little Cave” Curry if he ever felt unsafe, he told me about when he slipped on a rock stepping over a log and suffered a 3-inch puncture wound in his thigh while 15 miles from town. He said, “I bled a lot and went into shock. This made me feel unsafe.” Later in Maine, he was dive-bombed three times by a protective mother goshawk! Some luck.

But for most people, the risks are more mundane. Prevention of contracting Lyme disease is a major consideration. Check yourself every night at camp for ticks and consider treating your clothes with Permethrin. Proper food storage is not only a good “Leave No Trace” principle but also a good way to avoid any unfortunate hungry wildlife encounters.

When it comes to hitch-hiking to town, or “hitching,” it may be daunting, but it’s different around trail towns than it is in the rest of America. Locals recognize thru-hikers and are quick to help. That said, it’s always best to do it in a group. If you’d like to avoid hitching as much as possible, there are frequently “trail angels”—trusted folks who go out of their way to help hikers—and shuttles available.

You won’t want to believe it, but social issues—racism, homophobia, misogyny, transphobia and the like—unfortunately persist out on the trail. Depending on your identity, you’ll know what you’ve dealt with in the past and what you might face. You’ll be spending so much time alone with nature that if you do run into those experiences, they can feel jarring in a different way. So often, though, the community is warm and welcoming. When you find your people, you’ll be able to lean on them.

Where will you sleep on the A.T.?

One great thing unique to the A.T. will be your frequent access to shelters should you (or the weather) deem it necessary. The ATC reports that there are more than 250 along the entire trail, on average about 8 miles apart. Shelters are especially nice when it rains. They often have food storage available and are a nice place to congregate and swap stories with other hikers. They fill up quickly though, especially in the southern states at the beginning of the season. The shelters will frequently feature a privy (trail speak for toilet), but not always. It’s a good idea to be ready and able to “dig a cat hole.” When you do so, be sure to follow the LNT principles associated.

There are downsides to shelters—mice, mosquitoes and loud, impolite hikers make a habit of frequenting them as well. Luckily, shelters aren’t your only option. You can camp nearby, or elsewhere along the trail, so long as you’re eco-conscious. Evan “Couscous” Leonard is a big fan of hammocks, which are a viable camping choice along just about the entire A.T.! He says, “They’re finicky and take a lot of trial and error, but once your system is dialed there’s just no going back. I now take to the skies every chance I get.”

How much does it cost to hike the Appalachian Trail?

Finances can be tricky. If you don’t already have backpacking gear, it’s a big investment to make. Those limited by funds may just end up with heavier gear, as lightweight materials can cost a pretty penny—go figure. But don’t let that stop you!

When asking around for how much A.T. thru-hikers saved up beforehand, I got a variety of answers. Some said $2,000, some said $10,000, but more were somewhere in between. When you have all your gear and get onto the actual trail, it’s as expensive or cheap as you make it. Most of the money you’ll spend will be on food and places to stay in town. You can certainly plan out some resupplies beforehand and mail them to yourself, but it’s not a necessity. Be careful not to plan too far ahead, either, because your food tastes will certainly change the longer you’re hiking. If you want to save money, stay out of town. Get in, resupply, and get back out. You’ll find it’s easier said than done.

As far as permits and fees go, there aren’t many. There’s no permit required for the trail as a whole, though there is a voluntary registration system available through the ATC. You’ll need to get one permit ahead of time for Smoky Mountains National Park; it will cost you $20 if you get it before March 1, and $40 if you wait until after. You’ll need to obtain a permit in Shenandoah National Park and Baxter State Park, as well, but both are free and can be done in person. The White Mountains in New England charge $5 to $15 for camping, but there are a few work-for-stay options available there.

How much should I train to hike the A.T.?

The A.T. is full of young folks, older retirees, and everyone in between. The youth tend to get away with less physical preparation simply by virtue of their age. Hikers with a few more years behind them may want to work their way up to the mileage and elevation change that the A.T. will demand. Stronger leg muscles help protect your knees on those descents.

Realistically, it is almost impossible to get your body into perfect thru-hiking shape beforehand. Whatever training you get in will make the adjustment easier, but hiking all day, every day will feel like nothing else you’ve done. You’ll gain your “trail legs” eventually, but you’ll go through some pain first, and it’s your mental strength that will pull you through.

“I would have benefitted from some mental training because I struggled much more mentally than physically while on the trail,” says Molly Mol. You’ll hear a common refrain that you should really listen to: “Don’t quit on a bad day.”

Okay, but why would you do this?

“What is the A.T. to you?” I asked my hiking friends.

“The A.T. helped me figure out how I wanted to live my life,” said McGoober.

“Those woods feel like home, anywhere you step onto the trail,” Big Money said.

Captain Jack said: “The A.T. is my first love. The one that started it all. Something that could never be repeated, though I try and try and try.”

If you’re thinking about hiking the A.T., you should do it. Be warned, though: It will change your life, and there will be no going back.

Hello my names Tim and ive known about the AT for awhile now but this March I saw alot of posts and gear advertising so I decided to look deeper into it and ive decided to hike the AT NoBo the first week of March 2024 now I’ll be 47 at the time of my start date but I’m an active guy so for this year I’m going to read all I can get advise from other AT hikers and buy gear each month I preety much have all my gear picked out and for the last two or three months I’ll be training and working on preparing for this trip people say it will change your life and that’s what I’m hoping for…..Thank you all

Is there anybody I could go with that would hold my hand. I’m new at it and I always learn better when someone shows me

Tempted to try it at 62! Thanks for all the inside info.