After two decades of intense legal battle, 9.4 million acres of the nation’s largest national forest—the Tongass National Forest in southeast Alaska—will be protected from deforestation for good. The Biden Administration’s ruling, announced on January 25, repealed a Trump-era decision to reopen part of the Tongass to logging and road development.

Conservation advocates, recreationists, and local Indigenous tribes have celebrated the new ruling. The Tongass National Forest is home to many species Native Alaskans rely on for food. Deer and moose thrive in the deep woods, and the streams run thick with salmon.

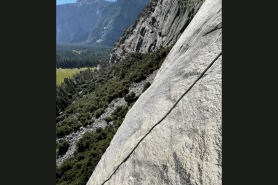

The land also holds incredible recreational potential. A swath of wilderness as big as West Virginia, the Tongass contains lush rainforest and glacier-encrusted peaks. In between, you’ll find 800-year-old trees, elusive packs of gray wolves, and more bears per square mile than anywhere else in the world. The backcountry exploration and wildlife-viewing opportunities are practically endless. In the summer, visitors can sea-kayak up and down the coastal islands. The winter, meanwhile, offers opportunities to spot the Northern Lights.

The other benefit to keeping roads and mines out of the Tongass is that the forest is a massive carbon sink. According to some estimates, its enormous trees absorb up to 30 percent of the greenhouse gasses emitted by the U.S. each year. Cutting down those trees for mineral extraction would cause erosion and the loss of old-growth forest, which absorb more carbon from the atmosphere than fast-growing young trees. Pumping oil, natural gas, or other resources from the ground beneath the Tongass would also release new carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, exacerbating the effects of climate change.

The decision to eliminate old-growth logging and ban new roads in the Tongass, therefore, is a big win for the environment, says U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack.

“As our nation’s largest national forest and the largest intact temperate rainforest in the world, the Tongass National Forest is key to conserving biodiversity and addressing the climate crisis,” Vilsack said in a statement.

Opponents of the new ban argue that it limits economic opportunity for local Alaskans. However, the New York Times reports that there are currently only 312 logging jobs in the area—down from more than 3,500 in 1991. The immediate economic effect of the ruling, therefore, may be relatively limited. In the meantime, the reinstated roadless rule could attract backpackers and other backcountry recreationists, which could boost local tourism.

“Restoring roadless protections listens to the voices of Tribal Nations and the people of Southeast Alaska,” Vilsack says, all “while recognizing the importance of fishing and tourism to the region’s economy.”