Women in the 60s couldn’t have a credit card or get an Ivy League education, but they still stood up for what they believed in, and many of them did what they could to improve life for current and future generations. In particular, many women throughout history have advocated for the outdoors. Here are four women who made amazing outdoor contributions in the 1960s.

Videos by Outdoors

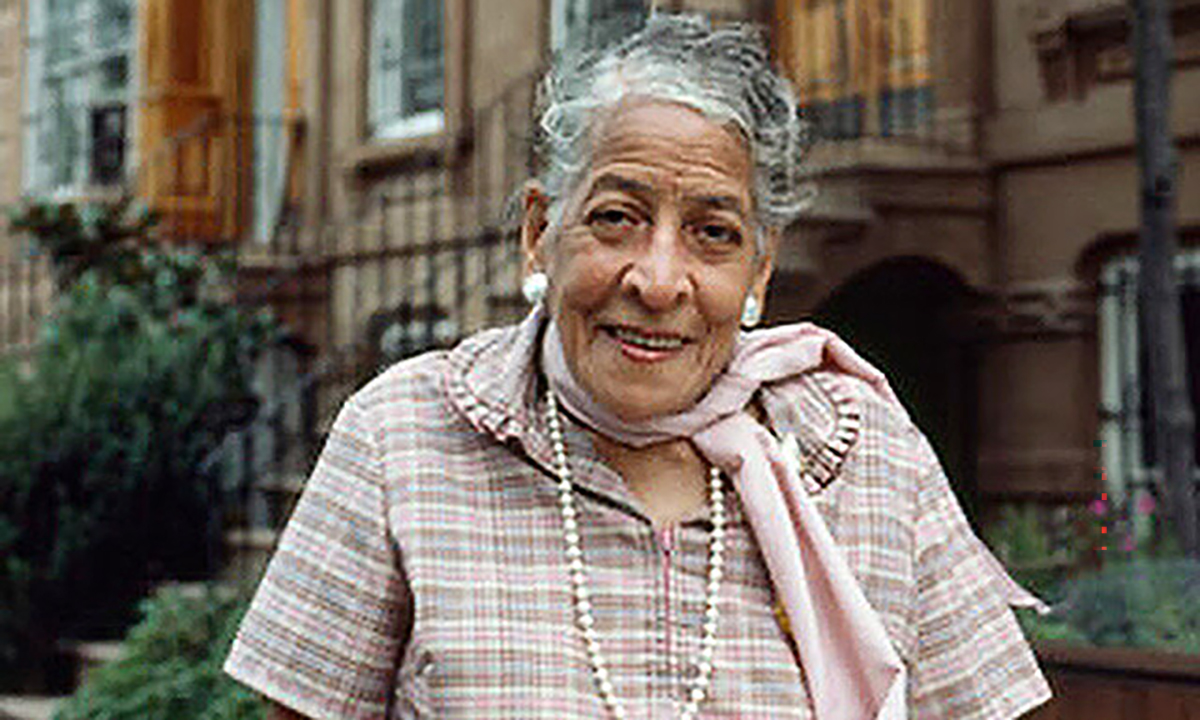

Hattie Carthan

A community-based environmental activist, Hattie Carthan was born on September 7, 1900 in Washington, D.C. She moved to Brooklyn in 1928, and in 1953, she moved to Bedford-Stuyvesant on a tree-lined block of Vernon Avenue. By 1964, only three trees remained on the block. Carthan saw the trees as precious commodities not only for their aesthetic value but also for their ability to provide shade, form habitats for wildlife, and create precious clean air amidst a bustling city.

She encouraged neighbors to form a block association—the T & T Vernon Avenue Block Association—to improve their neighborhood. One back-to-school block party for the children followed by several other parties raised enough money for her to purchase four saplings the following summer, thus beginning her efforts to regreen her neighborhood. John Lindsay, the New York Mayor, attended one of the block parties, and the City Parks Department provided trees under its tree-matching program.

Carthan founded the Bedford-Stuyvesant Beautification Committee in 1966 to continue her environmental stewardship. Overseeing 100 block associations, she spearheaded the planting of over 1,500 honey locust, sycamore, and ginkgo trees throughout Bed-Stuy. The committee was also awarded a grant in 1971 to teach youth about tree care and provide a stipend for summer work, known as the Neighborhood Tree Corps.

In 1968, developers threatened to cut down an endangered magnolia grandiflora to build apartments. Carthan led an effort to save the tree, securing a “living landmark status” for the tree in 1970 and earning the nickname the “tree lady of Brooklyn.”

She also raised funds to construct a protective wall behind the tree to shield it from a planned parking lot. Carthan purchased three brownstones set to be torn down for development near the tree and created the Magnolia Tree Earth Center of Bedford-Stuyvesant—an educational center focused on teaching youth the importance of taking care of trees.

Hattie Carthan passed away on April 23, 1984. The Magnolia Tree Earth Center of Bedford-Stuyvesant continues her missions to promote community sustainability and the greening of urban spaces. A mural at the Magnolia Tree Earth Center in Brooklyn celebrates Carthan’s life and contributions. Parks Commissioner Edwin L. Weisl Jr. honored her for distinguished service to the City of New York in 1975.

Hattie was also presented with the Brownstone Revival Committee’s first annual Genesis Award. A community garden created in 1985 was renamed Hattie Carthan Garden in 1998 and expanded to the Hattie Carthan Community Garden Farm in 2009. The Brooklyn Botanic Garden Research Center created a hybrid yellow magnolia and named it in her honor.

The 40-foot magnolia tree still stands.

“We’ve already lost too many trees, houses and people [. . .] your community – you owe something to it. I didn’t care to run.”

Hattie Carthan

Rachel Carson

Known as the founder of environmental science, Rachel Carson was born in Springdale, Pennsylvania in 1907 and spent her early years on her family’s farm. She attended the Pennsylvania College for Women, majoring in English and biology and went on to get her Master’s degree in zoology from Johns Hopkins University.

She began her career as a teacher before becoming an aquatic biologist. She wrote radio scripts for the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries and eventually became editor-in-chief of all publications for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Her award-winning book The Sea Around Us, spent 86 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list, prompting her to quit her work with the bureau to write and research full-time.

Best known for her work Silent Spring, which was released in 1962, Carson is responsible for bringing worldwide attention to insecticides’ effect on bird populations, especially DDT. It led to the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and highlighted the need for public health regulations.

Carson passed away in 1964 after a battle with breast cancer. Her work led to an eventual ban of DDT in the United States in 1973. She was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1980. The Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge is a 9,125-acre National Wildlife Refuge in Wells, ME named in her honor. Rachel Carson College was also created in 1972 as a residential college at the University of California, Santa Cruz, emphasizing sustainability and the environment.

“Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts.”

Rachel Carson

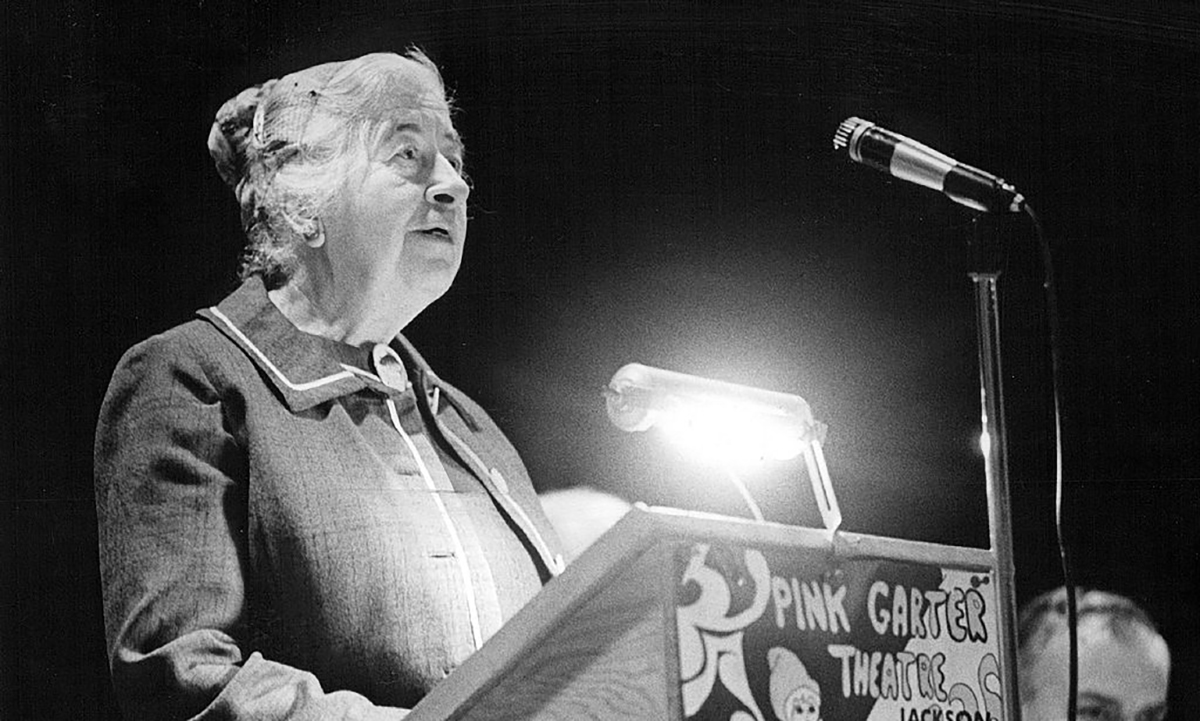

Margaret Murie

Margaret Murie was born in Seattle, Washington on August 18, 1902. Most of her youth was spent in Fairbanks, Alaska, where she became the first woman to graduate from the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines with a business administration degree.

Called the “Grandmother of the Conservation Movement” by both the Sierra Club and the Wilderness Society, Murie played a significant role in creating the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and passing the Wilderness Act.

Murie and her husband, who was working for the U.S. Bureau of Biological Survey at the time, honeymooned by taking an eight-month expedition in the Brooks Range studying caribou and birds. After that, Murie had visions of saving entire ecosystems. In 1956, she and her husband started a campaign to create the 8-million-acre Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, persuading then-President Eisenhower to sign off on it, with the help of U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas.

A memoir entitled Two in the Far North was published in 1962, and it chronicled Murie’s research expeditions to Alaska, as well as her marriage and early life. After her husband’s passing in 1963, Murie focused on continuing the conservation efforts they began together. She continued researching, made speeches, and traveled to environmental-based hearings. She also consulted with conservation groups, including Sierra Club and the National Park Service (NPS).

Murie and her husband played an instrumental role in passing the Wilderness Act in 1964, which created the legal definition of wilderness in the United States and protected 9.1 million acres of federal land in the U.S.

She spent her later years surveying potential wilderness areas for the NPS and working on the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act. Murie also spent a lot of time with her three children at the ranch she owned in Moose, Wyoming.

Murie received the Audubon Medal in 1980 and was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom from former-President Bill Clinton in 1998. She also received the John Muir Award in 1983 and the Robert Marshall Conservation Award in 1986. She received an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters from the University of Alaska and was made an honorary park ranger by the NPS.

She passed away on October 19, 2003 at the age of 101. Her residence in Moose was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1990. In 2006, the Murie Ranch was designated as a national landmark. A conservation institute named for Murie and her husband is found at the ranch.

“If we allow ourselves to be discouraged, we lose our power and momentum. That’s what I would say to you of these difficult times. If you are going to that place of intent to preserve the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge or the wild lands in Utah, you have to know how to dance.”

Margaret Murie as quoted in Two in the Far North

Celia Hunter

Growing up in a logging community in Arlington, Washington, Celia Hunter always had a sense of adventure. She admired Amelia Earhardt and decided at the age of 21 to learn to fly. She trained with the Women’s AirForce Service Pilot Program and ferried aircraft across the country during World War II.

Realizing her dream of flying in Alaska, Hunter and pilot friend Ginny Hill were hired to fly a couple of Stinson airplanes from Seattle to Fairbanks in December 1946. In 1947, Hunter decided to stay in Alaska, originally just looking to connect with nature, not necessarily to save it.

In 1952, Hunter, her friend who was now married and called Ginny Wood, and her friend’s husband Morton Wood opened Camp Denali on the the western edge of Denali National Park. Inspired by the hut systems in Europe, Camp Denali is said to be the start of ecotourism in the U.S.

In 1960, Hunter and Wood founded Alaska’s first statewide environmental organization called the Alaskan Conservation Society (ACS), beginning their campaigns to connect and save nature. Hunter and the ACS worked along Margaret and Olaus Murie to safeguard and establish the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge that same year. The ACS also worked on projects including the Rampart Dam and Project Chariot in the 60s.

Camp Denali was sold in 1975 to focus more efforts on environmental causes. In the late 70s, Hunter became the first female president of a conservation organization when she was named president of The Wilderness Society. Her persistence led to the creation of the Alaska Conservation Foundation in 1980. Hunter also worked to pass the 1980 Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) to protect over 100 million acres of federal land in Alaska.

She received the John Muir Award, the highest award from the Sierra Club, in 1991 for her lifetime dedication to conservation, followed by the Robert Marshall Award from the Wilderness Society in 1998. Hunter and Ginny Wood received the first-ever Lifetime Achievement Award from the Alaska Conservation Foundation for their roles in creating Camp Denali.

An endowment fund from the ACF bears her name for youth interested in environmental careers. Even in her last days at age 82 in 2001, Hunter wrote letters from her log cabin in Fairbanks to Congress about the need to protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge from oil drilling.

“You can’t have it both ways. Either you respect the wilderness quality of the environment and write it into law or you denigrate the condition of pristine nature and place the need for oil uppermost on your scale of values.”

Celia Hunter in November 1987 before a joint oversight hearing on the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

Have you ever visited the places these four extraordinary women helped preserve? Comment below if you have.