If you’re adventuring in the mountains, you’ll probably descend into a river valley at some stage. In the event that you’ve lost your way, rivers can offer a route to safety, as they often lead to towns, roads, bridges and eventually to a lake or the sea, and they offer an unlimited supply of water.

Videos by Outdoors

Rivers also pose dangers. In heavy rains, flash flooding can happen fast. River banks can have swamps, bogs or ravines that you can’t get through on foot and may be too fast-moving for safe rafting. In jungles, rivers can be home to dangerous animals such as piranha, crocodiles and alligators.

How to tell if a river is safe

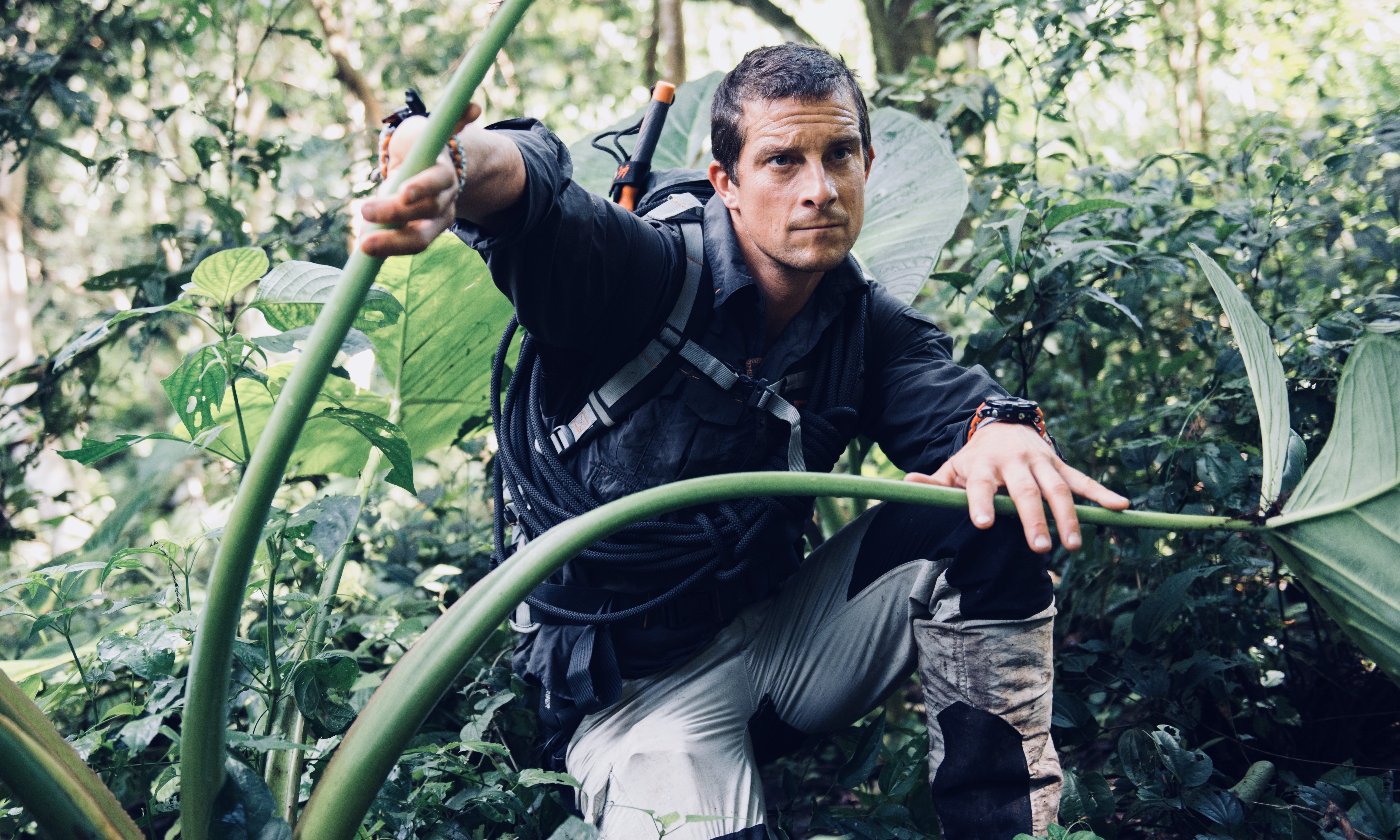

In order to determine whether a river is your route to salvation, “your first task will be to assess the risk that a river poses.” says Bear in Born Survivor.

To ascertain if a river is the best means of escape, Bear considers details like the water temperature and depth, the speed of the current, if he can see any obstacles up- or downstream and if the river is straight or has many bends.

And even if Bear determines the conditions are generally favorable and his best option is to float down it, he’ll also assess whether it makes sense to enter the river where he is, or walk some up- or downstream first.

Understand the risks of getting in

Cold water drains the body’s heat up to four times faster than cold air, according to the U.S. National Weather Service, creating a very real risk of hypothermia, even in water that doesn’t feel that cold. What’s more, rivers contain rocks, tree limbs and other debris that could cause injury below the water’s surface, not to mention variable currents and depths that could suck you under.

“In the Rockies, I almost suffered both [hypothermia and injury] and only just made it out of the rapids in one piece, shivered and battered,” says Bear. “It is smarter to keep clothes dry [and yourself out of the water] at all costs.”

It may be that crossing the river to the other bank may offer a better walking route. In that case, remember that rivers are usually narrower and shallower the further upstream you go—but keep in mind this may take you even further out of your way, as downhill is the best direction for escape.

Waterproof your gear as best you can

Once you’ve decided you’re going in, the name of the game is keeping as much of your gear as dry as possible. You’ll want to wear one underlayer of clothing; it won’t keep you warm but it will protect your skin against scrapes, and will be psychologically comforting. You can also keep your boots on to protect your feet and ankles, but take off your socks to keep them dry.

Bundle up your remaining clothes and encase them in a dry bag or plastic bag—you’ll want them dry for when you get out and need to warm up. Keep any tinder for fire you have in plastic bags as well; you can even use these bags tied together as your flotation devices.

If you have a knife, keep it close at hand in case you or the bags get caught up in underwater roots or branches.

Have a plan and don’t just dive in

In general, it’s best if you use the river as a temporary solution to get from point A to B, rather than a long-term cruise. Cold shock can set in within 2 to 3 minutes and can be just as dangerous in 50°F to 60°F water as it is from 35°F water.

Not only that, water as warm as 77°F can trigger irregular breathing if you suddenly submerge in it—plus, who knows what you might land on if you take to jumping in.

“Don’t dive in but wade in surely but slowly,” says Bear.

If the water is very cold, hypothermia can set in after about 10 minutes, so don’t plan to be in there long: Know where you are aiming for and how you will get out of the water.

Keep afloat any way you can

If your only way to save yourself is via the waterway, you may consider making a raft by lashing together logs, bamboo or other sturdy, floatable material available to you. However, rafts are most suited to jungle rivers, as in fast-moving mountain rivers, they can be smashed up by rocks.

For mountain rivers, Bear prefers to use a flotation device that will keep his head above water. This could be made by trapping air in the plastic bags holding your gear, or fashioned out of made from clothing like pant legs, filled with air and ferns, tied with string.

In a pinch, you can tie the legs of the pants themselves into knots at the ankles and swing them into the air to trap air like a balloon, then hold them tightly closed at the top or lash them with a belt. Another option is a backpack filled with empty plastic bottles.

“The secret is to hold your flotation device in front of you and not risk sinking it by putting all your weight on it,” says Bear.

Angle yourself so you travel down the river feet-first, so that you can use your feet to fend off any obstacles that you might hit. Keep to where the river flows the most evenly. On river bends, the current flows fastest on the outside.

Avoid rapids at all costs, but if you happen to get caught in them, aim for the “tongue” where most of the water flows. This should keep you away from protruding rocks. Also look out for whirlpools, where the water drops behind an obstacle. If you get caught in one, swim out and to the side as quickly as you can.

More from Bear Grylls:

- How to Make a Toothbrush in the Wild

- Driving in the Snow

- How to Build Shelter in a Forest

- How to Survive Sub-Zero Temperatures

- What to do If You’re Bitten by a Snake

- How to Navigate Without a Compass

- How to Deal with Injuries in Survival Situations

- How to Find Water in the Mountains

- Making Shelter in the Snow

- Priorities of Survival

- How Bear Grylls Lights a Fire

Pingback: How To Cross A River Like Bear Grylls – Outdoors.com